|

| Diego Velasquez, Portrait of Pedro de Barberana, 1631 |

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

— T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

So The Blackstone Group decided yesterday to

spin off its advisory business and merge it with Paul Taubman’s advisory “kiosk.” This is just the sort of relatively trivial exercise—the advisory group in question accounted for only 6.4% of Blackstone’s revenue and 2.1% of its economic income—that sets financial journalists’ and Wall Street pundits’ heads to nodding and chins to wagging, based almost entirely on the undeniable fact that Blackstone is big and important in the financial ecosystem.

1 But I must pop my head up from my hidey hole, if only briefly, to take issue with some of the hasty conclusions being drawn here. I promise to withdraw swiftly and silently at the conclusion.

First, I must disagree with

William Alden that Blackstone’s actions somehow contradict prevailing wisdom on Wall Street:

For decades, it has been a deeply held belief among many of Wall Street’s giants that a multiplicity of business lines is superior to a more streamlined model.

No, the conventional wisdom on Wall Street is and always has been quite simple: do whatever makes the most money. This is actually quite a sensible, beautiful, adaptable, and flexible business strategy. Sometimes, in fact, it does encourage executives to add business lines to their firms when they believe those businesses will add revenue and profit synergies to their existing business while being profitable in their own right (i.e., earning a return on top of paying for the people, assets, and financing costs they require). But more often than not it entails creating new products or services within

existing business lines (like derivatives within capital markets operations), or just hiring a bunch of clowns who can cover an industry or execute a kind of business you do not already perform. (A “business line” in my industry is frequently little more than a handful of guys with business cards and a budget.) Often, as in the current environment, it encourages senior executives to

discard unprofitable business lines, assets, or personnel by shutting them down, selling them, or just firing the unprofitable clowns because they can’t make money anymore or regulators are forcing you to get rid of unapproved activities.

Certainly there is a sensitivity among senior executives in finance to the benefits of maintaining a

portfolio of complementary business lines, wherein secular and cyclical variations in the fortunes of certain lines can offset the different variations of others, and often there is a corollary fondness for the diversification accomplished through sheer size alone (usually by executives of big firms, natch). But both these considerations take a back seat to the short-, intermediate-, and long-run profit contributions, both direct and indirect, by the business lines in question to the mother ship. You can suckle at the corporate teat for a little while in my business while you wait for conditions to turn, but patience in the Executive Suite runs out pretty quickly if you can’t pull your own weight over the intermediate and long term. And notice I wrote the business lines must be

complementary: if they don’t have the ability to contribute revenue and profit synergies to other business lines or the firm overall, their chance of staying within the fold long term—whether at GigantoBank or Two Guys and a Phone, LLC—are pretty darn slim.

2

Enforcing this strategy from the other direction, by the way, are the self-interested considerations of the personnel who run the business lines in question. If they calculate belonging to the mother ship does not enhance their own intermediate- and long-term earnings and personal wealth generation prospects (via subsidy in bad times and better pay in good times than they could achieve elsewhere), they have absolutely no hesitation to jump ship for sunnier shores. From the top of the firm to the bottom, very few successful people on Wall Street value their job title and business card more than the contents of their paycheck, and most of us act accordingly. Besides, managing a multiplicity of business lines is hard. Even Wall Streeters know we are

crap at management.

* * *So I think it’s fair to take Blackstone at their word when they say they are divesting their advisory business due to structural conflicts with their core asset management businesses. In other words, not only was the advisory business not contributing any meaningful profit or revenue to the main group (q.v. supra), but also belonging to Blackstone was throttling the advisory group’s growth and profit opportunities. One can see this clearly in their results, where the Restructuring group has advised on the lion’s share of the unit’s business this year, $32.4 billion worth of deals, versus the regular advisory group’s relatively paltry $4 billion. This makes sense, since restructuring advisory (think bankruptcy, turnarounds, and workouts) is its own special business, with a different set of clients (failing companies, creditor groups, distressed investors), revenue model (hefty monthly retainers versus deal success fees), advisors (lots of ex-lawyers with sharp elbows and fierce manners), and business cycles (naturally, they tend to do well when everyone else is flat on their backs). They should normally have few conflicts with Blackstone’s core asset management businesses, most of which tend to invest in healthy companies or assets. The major exception cited in the articles—their inability to advise Lehman on its bankruptcy because Blackstone’s real estate division wanted to bid on its assets—is the killer exception that proves both the rule and the magnitude of the potential conflict.

Given that conditions are booming in regular M&A markets, the lackluster performance of Blackstone’s corporate advisory business is telling. Because Blackstone is so big and so active in principal investing across private equity, real estate, securities, and other asset classes, they must constantly show up on one side or another of potential transactions which its advisory group would like to get hired for. Such direct conflicts will usually put the kibosh on Blackstone’s advisors getting hired, or at least severely limit their alternatives. And even if no direct conflicts obtain, many corporate clients and virtually all competing private equity firms and principal investors are no doubt reluctant to hire Steve Schwarzman’s trained killers to give them highly sensitive financial and strategic advice. I can’t help but think this goes double for the third leg of Blackstone’s advisory stool, which helps raise money for—wait for it—other asset managers.

The point, in other words, is that Blackstone divesting its advisory business has nothing to do with bucking a nonexistent trend on Wall Street to add business lines like barnacles on a freighter. Instead, it has everything to do with dumping business lines that add no value, subtract value, or fail to realize their own value due to inherent negative synergies resulting from persistent structural conflicts of interest with the parent company. In other words, it is business as usual.

* * *However, and for the very same reasons, Schwarzman pulling the ripcord on his M&A bankers does not signal the start of an industry-wide trend of divesting advisory groups by integrated investment banks. For one thing, big integrated investment banks with sales and trading, securities underwriting, and corporate advisory practices like the C-suite access top M&A and industry coverage bankers give them. Because they talk to the CEO, the CFO, and occasionally the Board of Directors, they have access to a level of decision making at corporate clients that the debt capital markets bankers and derivatives structurers do not. (They tend to talk to Treasurers or their finance staff.) This means they can get access to bigger, more profitable debt and derivatives deals and valuable, profitable product to pump into the insatiable maw of their huge trading machines. Profitable equity underwritings are also CEO- and Board-level prizes to give, and M&A deals are just icing on a cake that does not require meaningful capital to be put at risk.

M&A and corporate finance bankers like belonging to big integrated investment banks, too, when things work as they should. For one thing, it gives them more deals and ideas to talk about with their clients than just the usual who-should-buy-whom rigmarole. For another, it allows them to deepen and institutionalize their firm’s relationship with important clients by establishing multiple touch points and ongoing dialogues between subject matter experts within the bank and counterparts at the client. For a third, having equity research analysts who cover their clients and target industries gives them an entrée and a credibility with clients they do not know, and a capability to underwrite profitable equity business for those they do.

But most importantly, having M&A and industry bankers gives integrated investment banks an excuse to deliver ideas, industry and client insight, and all-important deal flow to the biggest-paying class of clients on Wall Street: private equity firms. While it is well known that private equity firms do not like paying M&A advisors for advice—usually because, rightly or wrongly, they think they know at least as much or more as bankers do about companies, deal-doing, and opportunities—they absolutely love paying investment banks to supply and arrange leveraged loans and high yield debt to finance buyouts of target companies. And banks love this too, because it is both huge and hugely profitable business. PE firms are usually happy to hire investment banks to sell their portfolio companies or take them public upon exit, too, although they tend to favor the banks which brought them the investment in the first place, financed it, and or smothered them with loving attention and juicy new buyout opportunities in the meantime.

So no wonder Blackstone ejected their M&A advisors. Not only can’t they offer the biggest and best paying clients on Wall Street (or anyone else) access to highly profitable leveraged lending, IPOs and equity underwriting, or sales and trading for securities and derivatives (because Blackstone Mère does not offer them), but also the biggest and best paying clients on Wall Street have no interest in hiring them because 1) they don’t value the advice they do have to offer and 2), duh, they work for one of their biggest competitors. I mean, if you could somehow engineer a similar set of constraints for Goldman Sachs’ M&A department, you can bet dollars to donuts the entire group would be camped out on West Street selling pencils before lunchtime.

* * *Lastly, I have to I disagree with Jeffrey Goldfarb, too. I don’t think this action will start any powerful trends toward consolidating independent M&A advisors like the new PJT-Blackstone Advisory spinoff or even any significant acquisitions of same by larger financial institutions. For one thing, there are only so many synergies and complementarities one can generate in a homogeneous business line like M&A advisory or restructuring before negative returns to scale begin to kick in. At the end of the day, firms like PJT-BA, Moelis, Greenhill, and Evercore are really just a loose collection of fiercely independent, egotistical rainmakers who focus almost entirely on mergers & acquisitions for corporate clients. There isn’t a lot of infrastructure or shared assets to leverage, and there are no complementary business lines like securities underwriting, derivatives structuring, or sales and trading to juice the vig. Managing an advisory boutique is almost exactly like herding a passel of recalcitrant cats, and in my experience, the more the cats, the harder the shepherd’s job becomes.

Similarly, the likelihood a large commercial or foreign bank would snatch up any of these independent advisory shops should be limited by sheer common sense. For one thing, if the acquirer does not already have most of the key complementary underwriting and securities businesses listed above, adding a costly team of pinstriped M&A advisors is going to be an expensive exercise in cultural frustration and no synergy. Adding such capabilities after the fact would be even more expensive and less reversible, since those businesses require real assets, infrastructure, and permanent fixed costs that dwarf those required by the usual M&A department. For another, the history of such acquisitions argues more eloquently than I can against it.

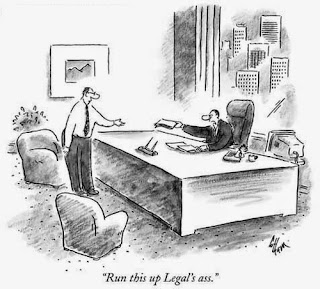

* * *For Steve Schwarzman, who has not paid noticeable attention to his old advisory business for years and who probably needed to be reminded by Tony James that Blackstone stilled owned it, the motivation for getting rid of the division is clear. He no longer wants or needs to be privy counselor to captains of industry or titans of finance.

It is many years since Steve Schwarzman has considered himself to be—and rightly so—a king in his own right.

Related reading:

Kiel Porter, David Carey, and Devin Banerjee, Blackstone to Spin Off Its Advisory Business With Taubman (Bloomberg, October 10, 2014)

William Alden, Shunning Wall Street Norms, Blackstone to Spin Off Its Advisory Group (DealBook, October 10, 2014)

Jeffrey Goldfarb, Blackstone’s Move Could Set Off a Trend (DealBook, October 10, 2014)

L’État, c’est moi (February 12, 2007) — Steve Schwarzman, Rex

Go West, Young Sheik (September 12, 2007) — Foreign bank acquisitions

Oxymoron (October 13, 2007) – Investment banking “management”

It’s Not the Meat, It’s the Motion (July 15, 2009) — Advisory boutiques

1 There is perhaps an ancillary motivation derived from investment bankers’ unwarranted glamour and notoriety due to their current popular role as B movie villains in our global financial crisis soap opera. But you already knew that.

2 This is not to deny that there are easy returns to scale (to a point) within business lines. Two Guys and a Phone, LLC would likely become much more profitable if it were One Hundred Guys and Several Phones, Inc., if only because they could share resources, support personnel, purchasing synergies, and enhanced marketing and sales generation prospects by looking bigger and hence more reputable to their potential clients, who are often big and diversified themselves. But these cost and revenue synergies often do not obtain between business lines that each have their own separate and different operating structures, client bases, and external market reputations. And past a certain point, scale and diversification can hurt you. The only thing belonging to GigantoBank ever did for me was open the door to an occasional new client who took a meeting because they were afraid GigantoBank would squash them (or more likely revoke their credit line) if they didn’t. A few others refused to meet with me because that is exactly what GigantoBank had already done.

© 2014 The Epicurean Dealmaker. All rights reserved.