[Fred] Joseph, the former Drexel CEO, said companies that don't pay bonuses risk losing employees who are unwilling to settle for salaries. Salaries in the industry range from about $80,000 to $600,000 a year.

"A lot of guys wouldn't want to work this hard just for salaries,'' he said. "You'd have a serious exodus from the business by a lot of really talented people—they'd become CFOs of companies, go to firms that didn't participate in the TARP program, go to hedge funds, or start hedge funds.''

God, Fred, I love ya dearly, but you've gotta stop granting interviews.

Fred Joseph, dusty old fart and erstwhile Pillager in Chief from the Dark Ages when Drexel Burnham Lambert stalked the earth, has simply been out of the game so long he doesn't realize we have traded in leather skullcaps for more modern headgear. To be fair, he is not alone among investment bankers in this regard, and the venerable old i-banking industry has been whipsawed through so many violent changes recently that it's leaving even us whippersnappers dazed and confused.

But times, as they say, are a-changin', and it's (past) time to wake up and smell the coffee.

In the Bloomberg article for which Mr. Joseph provided his pearls of wisdom, we do get some nicely understated insight from another Ancient Mariner:

Wall Street's chief executives will hunker down and pay bonuses this year in the face of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, a taxpayer bailout and mounting political outcry, industry veterans say.

Odds that Wall Street will forgo the payouts are "slim to none,'' said John Gutfreund, 79, president of New York-based Gutfreund & Co. and the former chief executive officer of Salomon Brothers Inc. "They're going to have to be a little bit sensitive because politicians, whether they like it or not, are part of their lives now.''

No shit, Sherlock.

With both Congress and the New York Attorney General's office crawling up the asses of major Wall Street firms with flashlights, Roto-rooters, and cattle prods looking for juicy little sound bites on excessive compensation for the Senate floor and the nightly news, it will be a long time indeed before investment bankers regain control of their compensation processes. If ever.

But listening to these two, a naïve observer might believe that massive year-end bonuses are a sacrosanct and ineluctable feature of employment within the industry. Henry Waxman, Andrew Cuomo, and the rest can just go pound sand, because nothing is going to change. Unfortunately—or fortunately, depending on how you view the subject—however, history, economics, and policy are arrayed against them.

* * *

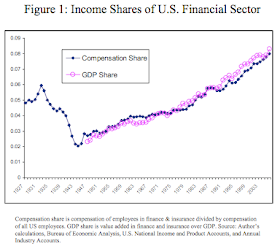

First, we have history. It seems that recent research cited by Zubin Jelveh at Odd Numbers gives evidence suggesting that financial sector employees have been substantially overpaid in recent years, coinciding with the credit bubble. A nifty chart tells the tale:

As Zubin remarks, "It implies that workers in finance are overpaid by 40 percent."

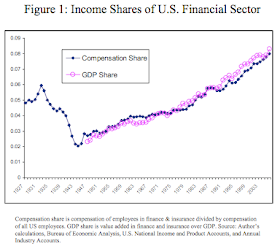

Another nifty chart, this time from a paper by Thomas Philippon (hat tip Zubin, again) demonstrates that aggregate compensation and share of total GDP has been climbing steadily in finance for years, and is now at levels substantially above long-run averages reaching back to 1927.

Phillipon's data also show that finance carries no God-given right to its current share of the national pie, since it averaged much closer to a 3 to 4 percent share of GDP during the Great Depression and post-war period, versus its current level of approximately double that.

The implications of this research are crystal clear, as Professor Philippon himself notes:

In April 2008, in an interview with Justin Lahart of the WSJ, my idea was translated in the following way: "Mr. Philippon argues that the surge of financial activity that began in 2002 created an employment bubble that is now bursting. His model suggests total employment in finance and insurance has to fall to 6.3 million to get back to historical norms, and that means losing an additional 700,000 jobs in the sector." In truth, my model is not about the number of jobs but about the GDP share, so it would be more accurate to say that the annual wage bill of the financial sector needs to shrink by approximately $100 billion.

Take your pick: 700,000 jobs lost in finance, or $100 billion less in aggregate compensation. Either way, that's a helluva lot of blood on the streets. And that conclusion, by the way, is based on the assumption that finance should account for approximately 7% of US GDP under normal circumstances. Does anyone out there believe we are passing through normal circumstances?

Given that this shrinkage is happening across the entire industry, show me an investment banker who is clueless enough to believe there is a better bid away if his or her own employer doesn't match his or her expectations. I will show you someone destined for the unemployment line.

* * *

Second, we have economics.

In his quote at the top of this post, Mr. Joseph trots out one of the hallowed shibboleths of i-bankers everywhere: "If banking doesn't work out, I've got options!" As a rule, investment bankers are unshakable in their conviction that no other class of human is quite so intelligent, attractive, or capable as they are. You cannot persuade them that there is any job in society or the economy they cannot undertake and master. (Perhaps this might explain why we have so many Goldman Sachs alumni stumbling around the corridors of 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue.)

Unfortunately, it does not appear that Ol' Fred has been reading a lot of newspapers recently. He mentions ex-bankers becoming CFOs of companies in the real economy, joining a bank not subject to the TARP restrictions and scrutiny, or sashaying off to hedge fund land. These ideas, to be blunt, are irredeemably stupid.

The last time I checked, a robust consensus had developed among virtually all conscious participants in our economy that we are headed into a long, deep, and nasty recession. Given that such travails tend to have a rather depressing effect on the financial performance of existing companies, and put a rather serious damper on the ability of new companies to find start-up financing and commence operations, where the hell does Mr. Joseph think all these CFO jobs are going to miraculously appear from? All the CFOs I know are desperately trying to hold onto their own crappy, high-pressure, thankless jobs, given that the current financial crisis has obliterated both their retirement accounts and any fond hopes they might have held about retiring early (or even on time). Furthermore, I know plenty of CFOs and CEOs in the real economy who would be absolutely delighted to suffer under the privations of a $600,000 annual salary sans bonus. Most of them work at least as hard and as long hours as any pissant thirty-something investment banker.

The CFOs and CEOs who historically have been compensated at levels the typical investment banker would consider barely adequate all tend to reside within the walls of the Fortune 1000 and their ilk. Even if all 2,000 of them get killed in a freak electrical storm at Davos next year, where are the other 698,000 of you going to find jobs?

Joining a bank not participating in the Bend Over and Take It Financial Stabilization Program directed through TARP is a joke, too. By the time this is all over, any bank which has not received an equity injection from the Treasury will be pushing up corporate daisies, since Henry Paulson will only decline to invest if he thinks a bank is going bust, and so far no bank has been given the option to decline Mr. Paulson's largess.

I can also tell you for a fact that independent i-bank boutiques, which have been advertised as the Great White Hope for unemployed dealmakers and rainmakers, are far too small to absorb more than a few hundred senior professionals worldwide. Furthermore, once most of these Big Swinging Dicks leave their huge, resource-rich bureacratic environments for the cold tundra of independent advisory work and have to start feeding their families with only what they kill themselves, you will begin to see a remarkable realization among most of them that they do not have an entrepreneurial bone in their bodies. All of a sudden, those grinding, low-paying, low-prestige CFO jobs they cannot get will begin to look pretty good to them.

And hedge funds. Hah! Given the little information we can glean from the media about conditions in that industry, the Darwinian bloodbath caused by the Great Unwind there is going to make Pol Pot's killing fields look like a friendly stickball game in a leafy suburb. The only reason hedge funds will be hiring new people in the next few years is to dig graves for the friends and colleagues they have shot, stabbed, and hacked to death in a desperate struggle to survive themselves. Most investment bankers would not recognize a shovel if their frustrated wife wrapped it around their head after having her credit cards declined.

* * *

Third, we have policy.

Forget politics. Put out of your mind the torch-bearing, pitchfork-waving mobs beating on the glass doors of every investment bank in New York. Ignore the ignorant, meretricious, pandering politicians who are gleefully piling on the battered corpse of the finance industry in order to win plaudits, votes, and campaign funds from their current and future constituents. (Although make sure you answer their subpoenas swiftly, with grace and humility.) Both groups will tire of their sport after a while and move on to the next hapless victim of mob vengeance.

No, just realize that eventually, after the usual witch hunts and occasional miscarriages of justice, this society will come around to a consensus that the investment banking and finance industries cannot continue in their current size and form. Parts of this transformation are already underway. When the last great survivors of three decades of consolidation, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, throw in the towel, convert to bank holding companies, and start offering free toasters to clients with every M&A deal and IPO closed, you know that a line has been crossed, once and for all.

Part of that line involves compensation. Structurally lower profitability, a multi-year exodus of surplus personnel, and direct and indirect regulation will take a serious toll on pay earned by the erstwhile Masters of the Universe. This is probably as it should be. While I do not agree with the common prejudice that investment bankers add absolutely nothing of value to the economy, I do believe that too large a portion of investment banks' role (and wage bill) over the past several years has been devoted to maintaining and speeding up the increasingly frenetic velocity of money circulating around the global financial system. Now that that velocity is slowing down, and excess leverage is bleeding out of the balloon, there is obviously less need for professionals whose jobs consisted primarily of inflating the bubble.

Regulation, too, will take its toll. I am not a big fan of regulation—not because I do not think well-designed, carefully implemented regulation can add value to an industry: I do—because I have little faith that real-world politicians and regulators won't botch things up and make conditions worse with silly rules, badly enforced. But there are no odds right now in opposing regulation: it is coming, whether we like it or not.

And history tells us that regulation of the financial services sector is not kind to its participants' pocketbooks. Citing yet another Philippon paper, Zubin Jelveh notes the following:

From 1900 to the mid-1930s, the financial sector was a high-education, high-wage industry. Its workforce was 17% more educated and paid at least 50% more than that of the rest of the private sector. A dramatic shift occurred during the 1930s. The financial sector started losing its high human capital status and it wage premium relative to the rest of the private sector. This trend continued after World War II until the late 1970s. By that time, wages in the financial sector were similar to wages in the rest of the economy. From 1980 onward, another shift occurred. The financial sector became a high-skill high-wage industry again. Even more strikingly, relative wages and relative education relative to the private sector went back almost exactly to their levels of the 1930s.

...

We find a very tight link between deregulation and human capital in the financial sector. Highly skilled labor left the financial industry in the wake of the depression era regulations, and started flowing back precisely when these regulations were removed.

This is not good news for the Ferrari dealerships in New York, Greenwich, or Mayfair.

* * *

So what can we conclude?

Pace the structural changes in the industry, which all point toward a long-term decline in both the absolute and relative levels of investment banking compensation, the CEOs and Boards of Directors of major commercial and investment banks are under severe short-term political pressure to reduce pay. Because this is true for the entire industry, senior management at the leading banks may take this opportunity to cut their wage bill in tandem from, say, the traditional 50% of net revenues to 40%, or lower.

I can think of many senior executives who would love to stick it to their restive, pain-in-the-ass bankers and traders who are never happy with their pay, no matter how high it is. This crisis could provide the industry great air cover for a structural change in the level of pay to employees. "It's not us," they will cry, "Congress made us do it!"

Nevertheless, even at reduced payouts the absolute level of pay for the typical bog-standard Managing Director will still be plenty large enough for Henry Waxman to string him up with piano wire on the steps of Capitol Hill and be applauded for doing so. Panicky, resentful voters who can only dream of making enough money to break into Obama's higher tax bracket and who are worried about keeping their homes, their jobs, and their three large-screen plasma TVs will not look kindly on anyone making over $1,000,000 this year. Even in a shitty year like this one, there will be plenty of those to go around.

So i-bank management better start getting pretty clever about justifying, explaining, and structuring its compensation practices and payouts in the glare of public scrutiny. For what it is worth, I think most people could accept even high pay packages if it were shown that bankers were not walking away with the family silver after the public has saved their house from burning down. Limit maximum cash compensation for everyone to less than $1 million, and make up any excess in the form of long-dated options and long-vesting restricted stock. I imagine even Joe the Plumber could accept an MD earning $10 million this year if he knew that $9 million of it was in the form of company stock he cannot touch for five to 10 years. That way, the banker will thrive or suffer in tandem with his firm's other shareholders and the US taxpayers who have rescued his cookies, and Messrs. Waxman and Cuomo will take comfort in knowing that TARP's billions have not flown straight out the door to fund cocaine and hooker binges on St. Barts this Christmas.

As every investment banker knows, money is what matters. But "optics," or how deals appear to the person on the outside, matters at least as much. Especially in these troubled times.

You have heard of windfall profits tax, no? Let's try to prevent the imposition of a "windfall bonus tax" this year, shall we?

© 2008 The Epicurean Dealmaker. All rights reserved.